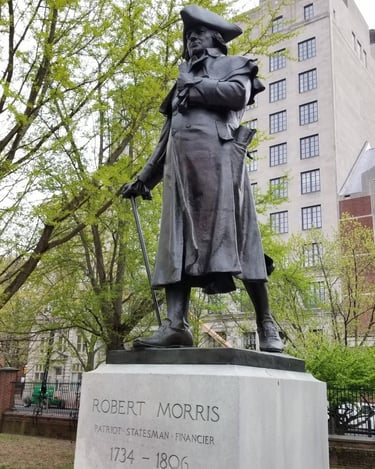

Underappreciated Heroes of the Revolution #4 - "The Financier of the Revolution"

This is Post #4 in my series on lesser-known heroes of the Revolutionary War period. Combining a little history and economics today, with the story of the man who almost single-handedly kept the Revolution going in all the practical ways - uniforms, weapons, and the money to pay soldiers. These days we just assume governments can go into debt to pay for things like these . . . but how do you convince someone to loan you the money? Easier said than done for a bunch of rebellious colonists! You need someone who already has those business connections - someone like Robert Morris.

Jay LeBlanc

11/20/20255 min read

OK, let's start with one of my favorite trivia questions - I used this one for years as an extra credit question on Revolutionary War or U.S. Constitution tests (depending on whether I was teaching history or civics at the time).

There are only two Founding Fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. Who are they?

Let's start by eliminating some of the most common guesses:

George Washington did sign the U.S. Constitution, but he was busy (some war thing 😁) in 1776 and 1781

John Adams did sign the Declaration of Independence, but was in France in 1781 and England in 1787

Samuel Adams did sign the Declaration and Articles, but opposed the U.S. Constitution effort

Thomas Jefferson did sign the Declaration, but was in France in both 1781 and 1787

Benjamin Franklin did sign the Declaration and U.S. Constitution, but he was in France in 1781

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were too young in 1776 to be involved with the Declaration

John Hancock obviously signed the Declaration and later the Articles, but was ill (and serving as Massachusetts governor) during the Constitutional Convention in 1787

So who is left? Well, for the numbers crunchers among you, there are 6 people who signed both the Declaration and the U.S. Constitution (including Ben Franklin, listed above); there are 16 people who signed both the Declaration and the Articles of Confederation (including Sam Adams and John Hancock); and 6 people who signed both the Articles of Confederation and U.S. Constitution.

One of the two correct answers is Roger Sherman of Connecticut, who I would love to get into more if/when we do a 250th Anniversary of the Constitution in another 12 years 🤔. And the other is the subject of this post - Robert Morris from Pennsylvania.

Unlike most of the legal minds represented among the Founding Fathers,

Robert Morris was first and foremost a businessman from the beginning.

His father established a business in the late 1740s shipping tobacco from

Maryland to England, and soon brought his son over to the New World as

an apprentice. When his father died abruptly in 1750, Robert at 16 found

himself learning on the fly and established a partnership with the Willing

family to establish Willing, Morris & Company as a more diversified

trading and shipping company, one that became very successful.

Robert's business connections helped him connect with patriot leaders

in Pennsylvania, first working against the Stamp Act and Intolerable Acts,

then helping supply PA militia with weapons and gunpowder as war began.

He was elected to the Second Continental Congress, and while initially he

voted not to declare independence he eventually signed the Declaration

of Independence with all the other delegates.

This account of Morris's actions during the war comes from the Bill of Rights Institute - "In addition to fundraising and recruiting other supporters, he also contributed significant personal resources to the war effort. After the signing of a Franco-American alliance in 1778, a French fleet arrived in the colonies. Morris supplied the ships during their time in America. In the brutally cold winter of 1780, the American army was suffering from desperately low supplies, and the soldiers had not been paid in months. Morris secured thousands of barrels of flour so that the troops could have bread and pledged his personal credit. Morris also appealed to several friends who together were responsible for supplying the army throughout the summer and fall of 1781. Morris sent his own money to fund the army to help propel it to victory in 1781. He sent much needed funds to Nathaniel Greene’s poorly-clad and underfed army fighting in the Carolinas during the key victories at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. More significantly, Morris paid for Washington’s troops to travel from New York to Virginia and then funded the Yorktown siege."

After the war Robert Morris found himself working with men like Alexander Hamilton to begin developing a longer-term solution to the new country's financial woes. However, Congress could request monetary support from the individual states, but the state governments were under no legal authority to honor these requests. Without Congress able to pay for the needs of the war, foreign diplomats during the war had to convince friendly European governments to loan them hard coin and gold. Now the Continental Congress was unwilling to approve any plan to deal with those debts or require the states to cooperate. In large part because of this, Morris became a strong supporter of a revision in the Articles, first with the proposed Annapolis Convention in 1786 to reform the Articles, and eventually the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to propose a whole new governmental system. He then served as one of Pennsylvania's first senators until 1795.

Unfortunately at the same time the country's financial system was finally getting on track (largely due to the efforts of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton), Robert Morris's own financial situation was growing dire. The debts he had personally assumed during the Revolutionary War to pay soldiers and buy military supplies had driven him to take on riskier business ventures, particularly involving land speculation. In the Financial Panic of 1797, Morris lost everything and ended up in debtor's prison for three years from 1798 to 1801. His estimated debt of $3 million dollars in that time period would be close to $100,000,000 today! Once released from prison, he and his wife declared bankruptcy and were able to live simple lives with a small pension until his death in 1806.

Today Robert Morris is little remembered for his role in keeping the Revolutionary War effort going with supplies and money - the only memory of his name is probably the small private university named after him in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is worth a reminder, though, of the final line in the Declaration of Independence (signed by Morris, among others) that the delegates would "... mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor". Robert Morris was a Founding Father who ended up living that sentiment out the hard way.

Robert Morris Education Resources:

"Robert Morris: America's Founding Capitalist", Morning Edition, from National Public Radio (NPR), Dec 2010, https://www.npr.org/2010/12/20/132051519/-robert-morris-america-s-founding-capitalist

LESSON PLAN Classroom Activity - "You May Depend Upon My Exertions: Robert Morris, the Revolutionary War, and Self‐Sacrifice", Bill of Rights Institute, https://billofrightsinstitute.org/lessons/may-depend-upon-exertions-robert-morris-revolutionary-war-self-sacrifice (Note the download links are at the bottom of each page)

"Robert Morris: The Financier of the American Revolution", American Battlefield Trust, updated Jun 2024, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/robert-morris-financier-american-revolution

"Bell Ringer: Pennsylvania Founding Father Robert Morris", C-SPAN Classroom, Mar 2017, https://www.c-span.org/classroom/document/?6282 (NOTE: Includes video and discussion questions)

LESSON PLAN Classroom Activity - "Money is a good soldier": Financing the Revolution", Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Aug 2015, https://hsp.org/education/unit-plans/economics-through-the-long-history-of-americas-first-bank/money-is-a-good-soldier-financing-the-revolution (Make sure you note the primary source links contained within the lesson)

"How Robert Morris’s “Magick” Money Saved the American Revolution", Journal of the American Revolution, Mar 2019, https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/03/how-robert-morriss-magick-money-saved-the-american-revolution/